Chapter 1

Washington, District of Colombia plays out in some strange ways. It is America’s Federal City, the nation’s capital. Sometimes it is re-imagined in a more global context, and referred to grandiosely as the Capital of the Free World or the Most Powerful City in the World. The locals simply call the place “the District.”

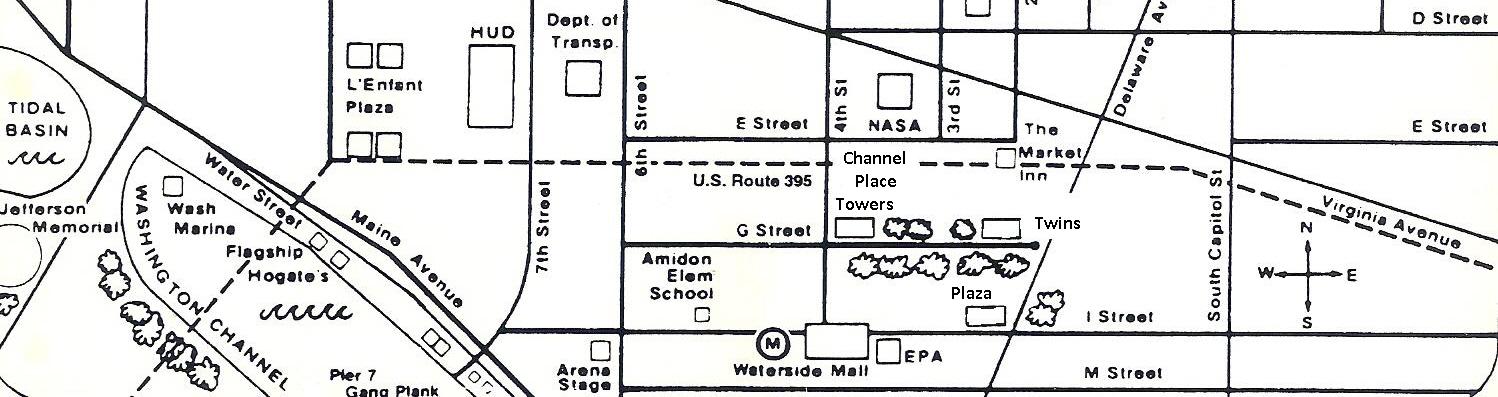

The neighborhood where I lived in the District was called Southwest. The city is geographically divided into quadrants, and while certain quadrants contained communities with catchy or historically significant names such as Capitol Hill or Georgetown, Southwest was just generically Southwest. More precisely, the Southwest neighborhood was the part of the quadrant situated above the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers, bounded roughly by South Capitol Street and the south side of the National Mall. Channel Place was the marketing name of the apartment complex in Southwest where I rented a one-bedroom apartment. (There was no road or locale actually called Channel Place, and most of the apartments had no view of the water.) The street address of my building was on I Street, often rendered in correspondence as Eye Street to avoid confusion between the letter I and the numeral 1.

I had moved into the Channel Place Plaza during the hot summer of 1999. I found there a quiet unprepossessing community of singles, couples, families, and retirees (representing forty nationalities, according to the friendly and effusive Mrs. Holliday, the Marketing Director of the properties). The apartment complex was an accidental microcosm of multiculturalism, diverse with none of the angst-ridden encumbrance of having to display politically correct “diversity” per se. The rent-rolls were flush with students and teachers laden with laptops and textbooks, professionals and tradesmen carrying their briefcases and tool-boxes, civil servants sporting their proximity cards on lanyards around their necks, and new parents pushing baby-carriages.

The neighbors were generally polite: they held open doors, pushed elevator buttons for one another, and acknowledged each other in passing, even if it was as brief as saying “Hey.” As a transplanted New Yorker, trading pleasantries was not something that came naturally to me, but I had grown accustomed to it over time. The people in the building were by and large good neighbors who put the collective effort into keeping Channel Place a place they were proud to call home, and little did any of them know this community was soon to be preserved only in memory–frozen there like some prehistoric insect sealed in amber.

Near the end of March 2003, a vexing, anonymous communication was distributed, slipped actually, under the doors of each household at the building. The three-page letter explained that our apartment complex, comprised of four buildings, had been secretly sold to a sleazy developer, and flat-out asserted that the sale was illegal. In boldface, it admonished that the owners had “deprived of us of a right” to own our apartments. The call to action was to organize as a tenants association. An invitation to attend an informational session in the lobby was slated for three days later. The letter was signed: “A Concerned Resident of the Plaza.” A quotation without attribution in the postscript read: “If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything.”

The letter may have raised as many questions as it did answers, but it certainly gave a fresh context to some cryptic but otherwise benign-sounding notices I had been receiving at intervals under my door from building management since the end of 2002. The letter also described a pattern of increasingly bad service at the building which I had heretofore believed was just my personal bad luck, but appeared to be more systemic.

If nothing else, the letter raised enough allegations of something not kosher that I wanted to learn more. So, apparently, did the seventy-odd residents who heeded the call to attend the building-wide meeting.

***

The lobby at the Plaza was filled on the seasonable evening of March 31, 2003. It was a representative cross-section of the building’s occupants. I had never seen so many of my neighbors in the same place at the same time. Most of the residents had taken the advice in the invitation and brought along a chair, although some stood around the periphery of the seated people.

The lighting as always was dim and florescent; the acoustics were poor. The noise of shifting chairs, shuffling paper, and random half-echoes of speech ricocheted throughout the lobby. Some of the folks who appeared to know each other well were pretty obviously couples. Others shifted around anxiously, uneasily, wondering, like myself, I suppose, what in the hell was going on at the building, and hoping for some answers. I had by now lived at Channel Place for three and a half years, without actually befriending many of my neighbors in that time, and that had actually suited me just fine. I noticed several familiar faces, many more less so. I did not see represented any of the households from my end of the first floor. Out of the hundreds of apartments at the building, I estimated the crowd consisted of roughly one-fifth of the units.

I positioned the white molded plastic deck-chair I had brought along for the meeting near the back of the lobby, close to an elevator bank. It was a fine vantage point from which to take in the scene and quietly scan the copious handouts that were given out: a proposed agenda for the meeting, a photocopy of an attorney’s bio from a law firm’s Website, and a preprinted note that residents were encouraged to include with their rent checks–stating that the rent was being paid “under protest” (whatever that meant). At the back of the papers was a tenants association membership application. The form had blank spaces for the usual contact information, and included a couple of lines where one could enumerate any special skills or willingness to volunteer time (I intended to leave that portion blank).

At the back of the lobby, a foursome of women of color faced the rest of the room. A makeshift dais had been fashioned from a folding card-table. A short-statured woman in retro eyeglass-frames, who appeared to be the brains behind the event, eventually called the meeting to order. She was dressed in youthful business clothes, but she appeared older than her wardrobe. She introduced herself as “Francine Montana, apartment 407.” Ms. Montana explained that she was a recent law-school graduate. She related that she had lived at Channel Place Plaza for four years but eventually wanted to relocate to New York State once she passed the bar exam.

According to Ms. Montana, not long ago she had received a new lease with a twelve percent rent increase, and had been denied the opportunity to file a Tenant Petition with the D.C. Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs over the substantial rent hike. Her research had led her to the D.C. Housing Finance Agency, who had, some months prior, approved a deal to convert Channel Place into an “affordable housing” project. The upshot of the deal was, ironically, to exempt Channel Place’s new owners from the rent-control regime which had previously guaranteed the residents predictable rent increases and owners a healthy rate of return.

While temping for a local trial lawyer, Francine Montana discovered, quite by accident, she assured us, more about what had really happened to our apartment complex. The firm where she had been assigned–Nesbit & Skelset, LLC–was already representing a tenants association that had been formed the previous November at two other buildings within our complex, known as the Channel Place Twins.

Innocuous as they may have looked on paper, the so-called renovations to the complex were several months farther along at the Twins. Complaints about the lack of notice and privacy, the inconveniences, the cheap materials, and shoddy work were already being documented by their tenants association. The argument was advanced that the renovations at the buildings were a tactic to harass and uproot long-term tenants before they could organize. The recommendation of Ms. Montana’s not to move out did not resonate with many. A collective dread was overtaking the room. There were expressions, verbal and facial, of shock and anger. Among others there was a look of disgust, as if they had just swallowed a mouthful of sour milk.

Montana encouraged our building to establish a tenants association, and spoke knowledgeably about articles of incorporation and bylaws, where to file them, and what the fees were. She asked for consent to set annual dues at ten dollars, and was ready with a receipt-book to accept payments. When questions arose, she said she’d take care of all the paperwork, and then Francine introduced the women at the front of the room who would be installed as interim directors for registration purposes.

The big, spectacled woman named Jan Granderson spoke first, teetering upon a worn wooden barstool that looked ready to give way under her prodigious weight. She mentioned that she lived in apartment 836, and added that she was an attorney. Then, she closed her eyes behind her thick lenses, peeking out from a tangle of nappy hair, and folded her arms across the top of her belly: that was her entire spiel.

The next person to introduce herself was Makeda Ebo-Jaimeson. She was a tallish and attractive woman who wore her hair up in a Rastafarian head-dress, who said she lived in apartment 240. She gave her occupation as minister. In response to a question from the floor, Ebo-Jaimeson said she was not affiliated with any particular congregation.

The last woman introduced herself as Monique Briscoe. She was seated, smiling, with dimpled cheeks revealed in stark relief under the otherwise unflattering overhead lights. In general appearance, she reminded me of a younger version of the performer Lena Horne. Briscoe’s head and eyes scanned the audience, but her hands rested primly and quietly in her lap. I recognized her from around the building. She was a gregarious affable lady of indeterminate age who always looked as if she was late for appointment and sometimes dressed like a church-lady. We had never introduced ourselves, but had certainly exchanged pleasantries by the mailboxes and in the elevators many times. Except for the slightest southern twang, I couldn’t place her accent, but she drove a sporty red late-model Pontiac Grand Prix which contained a clue–the car had Tennessee license tags, a slight oversight which Ms. Briscoe had obviously never bothered to correct within the proscribed sixty-day period. As she spoke that evening, the timbre of her voice and intonation strongly suggested to me that Monique Briscoe was as much a theater-person as she was a church-lady. “I’m in 841, and I’ve lived at the Plaza for seven years.… And I’m not a lawyer,” she added brightly, grinning, garnering some pent up laughter from the floor. (Even I thought it was funny, considering.) She was not the star of the show that night, but she had stage presence.

It was after these introductions were concluded that a tall middle-aged man formerly seated in the front row of the assembled stakeholders stood up and introduced himself as Ronald Feigenblich. In rapid-fire fashion said he was an attorney, a twelve-year resident of the building, and volunteered himself to take minutes of the meeting, whereupon he pulled his folding-chair around so that it faced the rest of us–in effect arrogating for himself the role of interim Secretary. He was extremely gaunt with ungainly gray hair and a crooked moustache. He had a yellow legal pad and a pencil. Nobody objected to his claim, or even the presumption, that it was “important” for him to be taking notes.

Ms. Montana then introduced some guests from the other buildings, officers of their tenants organization. Three women moved out from the shadows, each dressed in immaculate church-lady garb. The tallest, most church-lady-like among them, decked out in a black skirt-suit, a designer silk fichu, and glittering gaudy gold earrings was Jessica Downs, their President. Ms. Downs approached the card table, tottering in black patent-leather three-inch-heeled pumps.

“Fellow residents of Channel Place,” Downs began, “the long-term residents of the Twins have been waiting for years for the day to come when our buildings would come up for sale, at which time we planned to exercise our first right of refusal to buy the buildings and convert our rental apartments into condominiums. It is our right to organize and match the price of any bidder for the building. It is our right, but our rights are being ignored! And I will not have our rights ignored. Some of us have lived at the Twins for twenty years or more; many of us have anticipated the moment when we could own our own homes; but now it appears we’ve been hoodwinked. Now it appears the buildings have been illegally sold. Now it appears that our dream to own our homes has been thwarted. Now it appears that that the new owners want to turn our buildings into the projects. It doesn’t have to be this way!”

Ms. Downs was interrupted by a commotion spreading from the entrance to the lobby. Several uniformed police officers had appeared at the back of the room. The policemen just seemed to be observing, but their mere presence was vaguely ominous. Perhaps accustomed to viewing police procedurals on television, the expectation was to have the police announce their presence loudly. In any event, who had called law enforcement? Why had cops responded to this peaceful assembly? What was the charge? Weren’t there laws in the District making it illegal to file a false report? The atmosphere was charged.

“Don’t mind them,” Francine Montana said. “We’re just holding a meeting.” It was reported by Ms. Montana and corroborated by Ms. Downs that building management had called in the police in the past at the other buildings in the complex as Downs and others were organizing in what they repeatedly referred to as “public space.” Nobody asked the policemen what had brought them to the premises and the police made no effort to explain their presence.

“This,” Ms. Downs said, “is exactly what happened to us at the Twins. When they, the management, saw us organizing in our community room, the management called in the cops, hoping it might intimidate us. This is all part of management’s plan. Management wants to rid the buildings of all the long-term residents by chasing them out with all their renovations going on with the renters in place. At the Twins, we have retained architects who tell us that any necessary renovations to the premises would have gone smoother if the residents had been relocated temporarily to the other side of the building while the work was being done. At the Twins, we have retained an attorney who is willing to take up our cause, which is your cause, which is our fight for tenants’ rights. Rise up! Organize! Join this, our cause! Don’t let the bastards (God forgive me!) grind you down. Don’t let them lead you to believe this is over without a fight!”

Montana offered by way of postscript: “If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything.”

The Twins’s retained counsel, the Nesbit & Skelset firm, where Montana had once temped, was apparently willing to split its $20,000 retainer fee for representation between the Twin Towers and the Plaza, provided that the Plaza formed a tenants association and agreed to hire the firm. The Skelset firm was asking for a thirty-three percent contingency fee on top of the retainer. The Twins’s association was asking its members to contribute one hundred dollars per apartment as a litigation assessment to be applied toward the retainer fee. Ms. Downs indicated that the Twins tenants’ assessments were payable in two fifty-dollar installments the last of which was due by May 31.

There seemed scant interest in signing up for legal representation on the spot, but the necessity of having to organize a tenants association seemed a foregone conclusion to most. It was suggested from the floor that as people were recognized to speak that they give their names and apartment numbers to facilitate getting to know one’s neighbors. The momentum of the moment created the catalyst to solidify the interest in a more formalized organizational union.

By a vote of hands, it was resolved that annual dues were to be set at ten dollars. Francine Montana (407), Jan Granderson (836), Makeda Ebo-Jaimeson (241), Monique Briscoe (841), and Ronald Feigenblich (826) were approved as the interim directors of the tenants association. After this substantive groundwork was laid, other people volunteered their talents. A resident Web-head–Gerry Peterman (812)–offered to design a dedicated site on the Internet. Another tenant–Marc Moore (139)–volunteered to set up an online chat-room. Buck Didier (209) said he would serve as Sergeant-at-Arms/Parliamentarian. Jaycee Duncan (642) volunteered to work on a newsletter.

By this point, the meeting had gone on for sixty-five minutes, and a sense of emotional exhaustion had largely overtaken the room. Motions to meet again in a week and adjourn the meeting were proposed, seconded, debated, and carried. As the meeting broke up, I went upstairs to retrieve my checkbook, and I took a minute to fill out the membership form. The television flickered real-time images of a motorized convoy of American troops under small-arms fire jouncing along a barren sand-swept highway, closing in, inexorably it appeared, on a remaining pocket of resistance near the occupied Iraqi capital, Baghdad.

Back downstairs, there were still a few people queued up in front of me as I waited to hand over my check and my membership application to the tenants association. Francine Montana was accepting the checks and applications. Monique Briscoe was still present, ensconced in her seat, her hands still primly placed in her lap. Briscoe and I made eye-contact.

“Is this for real?” I asked Ms. Briscoe.

“Yes. I think it is,” she replied, looking up at me from her seat. “Are you going to support us?”

“I’m supporting the formation of a tenants association,” I said, in a tone meant to answer her question but not any prayers beyond that. I may have come across sounding like an asshole, but I intended to commit to nothing further for the time being. “That’s why I’m here now,” I continued, drawing her attention to the green faux-leather checkbook in my hand. “So, in the interest of full disclosure,” I said, smiling now, “my name is Daniel Dreitzler. I live in apartment 101.” Then I asked Briscoe: “Who wrote the letter, the one I got under my door that brought us all here?”

“I don’t know,” Briscoe replied.

I eventually asked the same question of Ms. Montana as I handed over my check and membership application. She said she didn’t know the name of the letter’s author. I found her answer less credulous.